- Home

- Garrett Robinson

Blood Lust Page 10

Blood Lust Read online

Page 10

Sun turned back, looking up at Albern. “You will keep telling the story if I come with you?”

Albern’s smile widened. “Until the tale’s true end.”

Her pulse raced. Her breath seemed to catch in her throat, and she was not sure she could feel her fingers. But she stepped up next to Albern’s horse, and as he nudged it to a walk, Sun followed.

She expected Albern to continue the tale immediately, but as they left the town heading south and passed into open country, still he remained silent. He only made gentle noises to the horse as he nudged it one way or another. Sun gave the steed another glance, half expecting to see the roan gelding from his tale. But that was ridiculous, of course. That had been decades ago. This horse was a deep chestnut brown.

“What are you thinking, child?”

Sun had been thinking many things, but none seemed like the right answer. So she asked him the question that had not left her mind, despite his reassurances. “Did all of this really happen?”

Albern cocked his head. “I told you already that stories are—”

“—Are meant to be learned from, yes,” said Sun. “I understand, but … how can you expect me to take it to heart, to learn from it, if I do not know for certain that it even took place as you say it did?”

Albern looked at her askance. “Do you think I am certain of how it happened?”

“I … what?” said Sun, frowning up at him. “Of course you are. You lived it.”

“Hm,” said Albern. “I see the lesson still has not taken root. Let me ask you this, then. Tonight you told me your name, but you left out your family name. Do you know if that answer was true or not?”

“Of course I do,” said Sun. “I knew what the truth was, though I did not speak it.”

“Mayhap. Or mayhap, in crafting a lie, you struck upon a deeper truth.”

She frowned. “I do not understand.”

“Do you really think you are still the noble daughter who first entered that tavern?” Albern chuckled. “I doubt she would have gone scarpering off with a decrepit, one-armed man. Those sound like the actions of a girl with no family, the actions of Sun of No Name.”

This was almost too much. Sun’s thoughts spun, and her feelings gave her no peace. She had often wished she was not a daughter of the family Valgun, but she was. Was she not?

Her parents’ guards must have reported that she had gone missing by now. She knew there would be consequences, and that they would be worse the longer she remained away. Yet she was not returning to her family, but traipsing off with an old man, simply because he was telling her a good story.

That did not seem very like something Sun of the family Valgun would do.

Her mind whirled, and she felt that strange, unmoored feeling again.

“Why are you telling me all this, about Northwood and the rest of it?” she asked. “Why will you not tell me what happened to your arm, or what happened to Mag?”

“Because you want to hear one story, Sun, but you need to hear another,” said Albern. “Any talespinner must seek a balance. He must tell the listener what they need to hear, but tell it well enough that the audience is willing to stay and listen, no matter what they demanded in the first place. Do you think, when your Dulmish king brings a skald into her court, that she merely searches out the one with the best voice? No, not if she is wise. She seeks the skald who will tell her the stories she most needs told, even—mayhap especially—when she does not want to hear them.”

“So you think you know better than me what story I need to hear?” said Sun. “You are just like my parents, and that is no compliment.”

“I think I do, yes,” said Albern mildly. “But if I judge correctly, I am different from your parents in one important respect: if you do not wish to take my advice, I will not force it upon you. You are free to go at any time—or, if you wish, you can simply ask me to stop telling the tale, and we can talk of other things.”

“You compare yourself to a skald,” said Sun. “Yet if a king demands a tale, her skald will tell it if he is a true servant.”

Albern’s eyes flashed as he looked at her, and for the first time he appeared truly angry. “You vastly misjudge us both if you call me a servant and yourself my king.”

Hot blood rushed into her cheeks. “I am sorry. I did not mean it like that.”

He held her gaze for a long moment. But then the hostility in his expression faded somewhat. “No, I suppose you did not. It is clear to me—forgive me for saying so—but I would guess you have little opportunity to exercise your skill at argument. I would wager that people in your life have been of two kinds: those who obey you, and those who you must obey without question.”

“Is it so obvious?”

“As obvious as the fact you come from Dulmun. You walk like you wear a crown, and those leathers of yours are hardly Dorsean, nor are they the garb of a poor commoner. I knew nothing about you when you stepped through the door of that tavern, but you told me much in the way you moved and spoke. And you are avoiding my point.”

Sun still did not wish to look at him, for her cheeks still burned with shame at the way she had spoken to him before. “What point is that?”

He fixed her with a look. “I am trying to tell you the story you need, Sun of the family Valgun. Yes, I know your family name as well. I think I know what you need to hear, and I am certain I know how badly you need to hear it. But I am trying, also, to make it a tale worth your time. Have I done a good enough job so far? Do you want to hear more?”

Sun felt many things. She was frightened, uncertain, and more than a little apprehensive about the shadowed wilderness they now rode through.

But above all of that, when she looked deep into her own heart, she had to admit one thing: she did want to hear what happened next.

“Yes,” she said quietly. Then, louder, “Yes. Tell me. Please.”

I TOLD YOU OF MAG fetching her spear from the Reeve. You should know something of that spear, before I continue the tale.

You had heard, before I told you, of Mag’s prowess in battle. But whatever you have heard, and however well I myself describe it, all tales are inadequate. Never have I seen or heard of such a master when it comes to combat. Her mastery extended to any weapon—in the battle of Northwood, she fought with a sword, you remember—but she became truly terrifying when her spear was in her hands.

I was with her when she got that spear, as it happens. We were in the western reaches of Dulmun. I had persuaded her to join the Silver Stirrups for a time, and that company had been summoned there for … sky above, I cannot remember. We were there for months, yet I cannot remember the conflict that brought us. Yet I remember every detail of the moment Mag found her spear. It is often that way when we age, and our memory begins to fail us.

The two of us had been given a day’s leave, and we were spending it in Vaksom, the city that sprang up around the warlight Arod. It was my first time visiting Dulmun, and I found myself uncomfortable—meaning no offense. To an outsider, your people appear quick not only to laugh, but also to anger, and they almost seem to enjoy settling disagreements with their fists. It left me feeling on edge.

But Mag seemed curiously at home in Vaksom. It was strange to see the way she looked at everything, as if she was trying to solve a mystery. Her head was cocked and her eyes were narrowed, and it seemed that half-hidden thoughts swirled around each other in her mind.

“What is it, Mag?” I asked her. “You look pleased to be here, and at the same time confused.”

“I suppose both are true,” she said. “There is something familiar about this place, though I have never been here that I recall.”

“Mayhap you came here as a child?” I said.

“Mayhap,” she murmured.

Suddenly she stopped dead in the street, staring at a shop. I looked it over. It seemed to be the shop of a bladesmith, but a far grander one than I had ever seen. Two stories tall it stood. Its front windows were open, and in them were disp

layed blades of the highest quality. I saw swords, daggers, and spears, but also many strange weapons that I had never seen the like of. Too, I had never seen a smithy with someone standing guard, but there was one here—a large brute of a man with horribly scarred hands.

“You have good taste,” I told Mag. “But I think your eyes are larger than your purse. Sellswords such as us could not bring the custom a place like this demands.”

Mag did not appear to hear me. She only stepped towards the shop’s door. As she approached, the guard barred her way and held up a hand.

“Stay yourself,” he said, his voice rumbling like an ocean wave. “What business do you have here?”

“What sort of business do you expect?” said Mag. “I wish to buy a weapon.”

The guard eyed her up and down. “You are no customer of this place. Begone.”

“You do not know how much coin I am carrying,” countered Mag.

“You could not carry enough coin on your person, and since you do not have a pack horse behind you—”

“Friend,” I said quickly. “You are a hired sword like us, are you not?”

The guard’s mouth twisted. “Not like you.”

I spread my hands wide, giving him a friendly smile. “Oh, not a mercenary, certainly. But we all have something in common: we are paid to fight. You have a greater appreciation for the art of battle than most people could imagine—as do we. And my friend here is special. I swear to you that you have never seen her like in combat.”

The guard arched an eyebrow as he looked down at Mag, who stood a good two heads shorter than he. “If you mean to intimidate me, you are not doing a good job.”

“Not at all,” I said. “But when someone ascends to her lofty heights of skill, they gain a rarefied taste for weapons of war. You may be right: we may not have enough coin to afford your master’s astonishing wares. But can you not understand a desire to simply see them? Let her at least have the dream of fighting with such tools of war, though they may be fit only for the nobility who pay our wages.”

His expression did not change a whit, and I thought my words had been for nothing—and, too, I feared that Mag might escalate matters, for that was a bad habit of hers in those days. But after a moment the guard drew aside, waving an admonishing finger at both of us.

“Disturb nothing,” he said. “Touch nothing. And do not approach my master if she does not speak to you first.”

“You have our word,” I said, nodding my thanks and ushering Mag into the shop.

“I could have taken him,” Mag muttered once we were safely away from the man.

“I know you could have,” I said. “But it might have put a damper on our experience here. Now you can peruse the weapons without worrying about constables showing up.”

It is customary for shopkeepers to put their finest wares on display in the windows, using them to draw in customers. But I could hardly have said the weapons in the window were any better than the ones we found inside. Every new blade I saw seemed to be the finest I had ever beheld, until I saw the next one. I am and have always been an archer first and foremost, but I know my way around a sword, and I found myself transfixed by those on display. They were made in the Dulmun fashion—longer and heavier than those in Calentin—but that did not prevent me from appreciating their quality.

After a moment I looked up and realized that Mag and I had become separated. I sought her out quickly, as I still did not trust her not to make trouble if anyone should bother her. I found her standing before a display of spears. The weapons were arranged in racks that held half a dozen each. These were no long infantry spears, meant for fighting in formation, and which are usually much taller than the soldiers that wield them. These were Dulmish dueling spears. If you have never seen one, they can appear a bit strange. They are usually only a little taller than the shoulder—just long enough to serve as a walking stick, not so long that they are burdensome for long journeys. Their spearheads are larger than those of infantry spears, and they have long edges so that they can be used to slice and cut, not just to pierce. There are smaller, curved blades just behind the head, almost like a hilt, that you can use to entrap and entangle the weapon of your opponent.

I had never seen anyone wield such a weapon before—after all, most of the battles I had seen had been formation fighting. It struck me as curious that Mag was so transfixed by the weapons, for I had had no inkling that she knew how to use them.

“Mag?” I said, for she did not appear to have seen me. “What is it?”

“These spears,” she muttered, and it sounded almost as if she was talking to herself. “I … I almost remember.”

“Remember what?”

She only shook her head. And then came a voice from close by, startling both of us out of our thoughts.

“It is rare to have someone lavish so much attention on my spears.”

Mag and I turned quickly. Before us stood the woman who I knew must be the master of this shop. She was of medium height, but as broad as a barn. Her arms, like any good blacksmith’s, were thicker than my thighs, and her torso had several more layers of weight over thick muscles. The back of her hair was done up in a tail, but the front cascaded like the wings of a crow wrapped around her moon-shaped face. Over her shoulder, I saw the door guard surveying us, his face stern but impassive.

“Do we have the honor of addressing the owner of this fine establishment?” I said, speaking just loud enough that I hoped the guard could hear my courtesy.

“You do,” said the smith. “Smedda of the family Stalhert is my name.”

“I am Albern of the family Telfer,” I told her, placing a hand over my heart. “And this is Mag.”

Smedda cocked her head. “Sellswords, I suppose. What brings you to my shop?”

“Why, only the desire to gaze upon your incomparable wares,” I said.

“Flattering,” said Smedda. “I am not in the habit of entertaining those who wish to peruse and not to buy, but courteous words can go far in changing my mind. I imagine you did much the same to Bronhil at the door, or he would not have let you in.”

“We impressed upon your noblest and most loyal servant,” I said, projecting my voice in Bronhil’s direction with all my might, “that our appreciation for your work was nearly limitless. Truly, your purse must overflow with wealth from grateful patrons.”

“Only one patron, really,” said Smedda. “King Lannolf, of the family Valgun. Once I secured his custom, it is rare to find anyone else who can match the coin my wares fetch.”

I had two curious sensations at the same time: I felt as though the walls were pressing in upon me, and at the same time it was as if I had shrunk to the size of a mouse, and the shop had become incomprehensibly vast. I gasped suddenly, realizing that I had forgotten to breathe for the space of several long heartbeats.

“You are King Lannolf’s armorer,” I said, my voice a mouse’s squeak. Mag had stopped paying attention to the conversation and was looking at the spears again. I smacked her hard between the shoulder blades, trying to get her to turn around. She ignored me.

“I am one of his smiths,” said Smedda. “He has others. And I rarely attempt armor. It is not my passion, and therefore my work is not as good as it could be. But when it comes to weapons: yes, I arm the king, and all his kin, and anyone else who catches his favor or fancy. And I am well rewarded for it.”

At once I dropped into a deep bow. I noticed that Mag still seemed to be paying no attention to what we were saying, and I smacked her again. “It is our deepest honor to be in your presence.”

“I can tell,” said Smedda, eyeing Mag, who had not stirred despite my actions. “May I ask why you are so—”

“What do you call them?” said Mag, turning suddenly and pointing at the spears. “I have never … that is, I do not recall ever seeing spears like this before.”

“They are rare, even here in Dulmun, and I have seen them nowhere else,” said Smedda. She stepped past Mag and lifted one

of the spears from its rack, lowering it and running her fingers along its length. “They are called spontoons. Meant for a single fighter, not for soldiers in formation, but then you can tell that. Nobles today rarely seek them out, for they are not considered ‘fashionable’—which just goes to show you how useless fashion is. If two fighters of equal skill face each other, one with a sword and one with a spontoon, I would bet half my considerable fortune on the one with the spear, every time.”

“They are a weapon of Dulmun?” said Mag, as though she had not heard anything Smedda had said after that.

“They are,” said Smedda. “The skill of their making was passed to me by my master, whose family has dwelled here since the time of Roth. As I said, I have never seen them in any of the other kingdoms, and I have visited all of them.” She cocked her head again and regarded Mag carefully. “Would you like to feel it in your hands?”

“Yes,” said Mag at once.

“Mag,” I said, “are you sure that is wise? If you were to damage it in any way—”

“Do not worry,” said Smedda. “I will not hold you accountable. There is a light in your friend’s eyes, and I wish to see what it might illuminate. I have a small yard in back of my shop. Choose whichever spear you wish, and meet me there.”

She set off for the back of the building at once, leaving Mag alone to choose her spear in peace. But Mag hardly seemed to need the privacy—she scarcely glanced at the rack before selecting one of the spears. Its haft was somewhat thicker than the others, its head a bit broader and a bit shorter.

Mostly, I noticed that it looked to be the most expensive spear on the rack. Mag had that habit, too—walking into any shop and choosing among its wares at random, she would inevitably gravitate towards the priciest item in the place.

But that thought fled my mind as Mag handled the spear. She tossed it lightly from hand to hand, and then she spun it on either side of her like a staff. The movement was natural and fluid. That was hardly a surprise, for I had seen Mag with all sorts of weaponry, and she was always formidable. But I could tell at once that this was different. The spear had become part of her almost from the moment she laid her hand upon it. Thunder did not crash in the sky, but it felt like it should have. A shaft of sunlight did not pierce through a high window to illuminate her, but it felt less like something that had not happened, and more like something that should have happened, but which the sky had forgotten about.

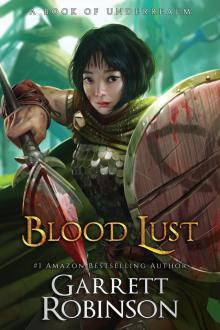

Blood Lust

Blood Lust The Tales of the Wanderer Volume One: A Book of Underrealm (The Underrealm Volumes 4)

The Tales of the Wanderer Volume One: A Book of Underrealm (The Underrealm Volumes 4) Darkfire: A Book of Underrealm

Darkfire: A Book of Underrealm Weremage: A Book of Underrealm (The Nightblade Epic 5)

Weremage: A Book of Underrealm (The Nightblade Epic 5) Realm Keepers: Episode One (A Young Adult Fantasy) (Realm Keepers Episodes)

Realm Keepers: Episode One (A Young Adult Fantasy) (Realm Keepers Episodes) The Academy Journals Volume One: A Book of Underrealm (The Underrealm Volumes 3)

The Academy Journals Volume One: A Book of Underrealm (The Underrealm Volumes 3) The Mindmage's Wrath: A Book of Underrealm (The Academy Journals 2)

The Mindmage's Wrath: A Book of Underrealm (The Academy Journals 2) The Alchemist's Touch

The Alchemist's Touch The Firemage's Vengeance

The Firemage's Vengeance Yerrin: A Book of Underrealm (The Nightblade Epic 6)

Yerrin: A Book of Underrealm (The Nightblade Epic 6) Midrealm

Midrealm Mystic: A Book of Underrealm

Mystic: A Book of Underrealm Shadeborn: A Book of Underrealm

Shadeborn: A Book of Underrealm Wyrmspire (Realm Keepers Book 2)

Wyrmspire (Realm Keepers Book 2) The Academy Journals Volume One_A Book of Underrealm

The Academy Journals Volume One_A Book of Underrealm